Why Blockchain Art Supply Is Radically Different

Let's compare traditional artists' supply vs digital artists' supply and a new way to think about it

Hello friends!

Over the past weeks, I’ve seen recurring conversations around digital artists’ supply. From Zancan’s open edition drop, PROOF setting a minting cap on GRAILS Season 3, and ArtBlocks collections being much smaller than before, the number of editions and the effect on the long-term value is widely popular and sometimes controversial.

I looked at the traditional art world to understand the supply from the masters and compare it to leading digital artists. I also highlighted some of the main differences, as, in my opinion, both worlds aren’t the same.

Finally, I came up with two ideas, or mental models, that ideally help digital artists and collectors when thinking about edition sizes and supply.

Traditional artists supply

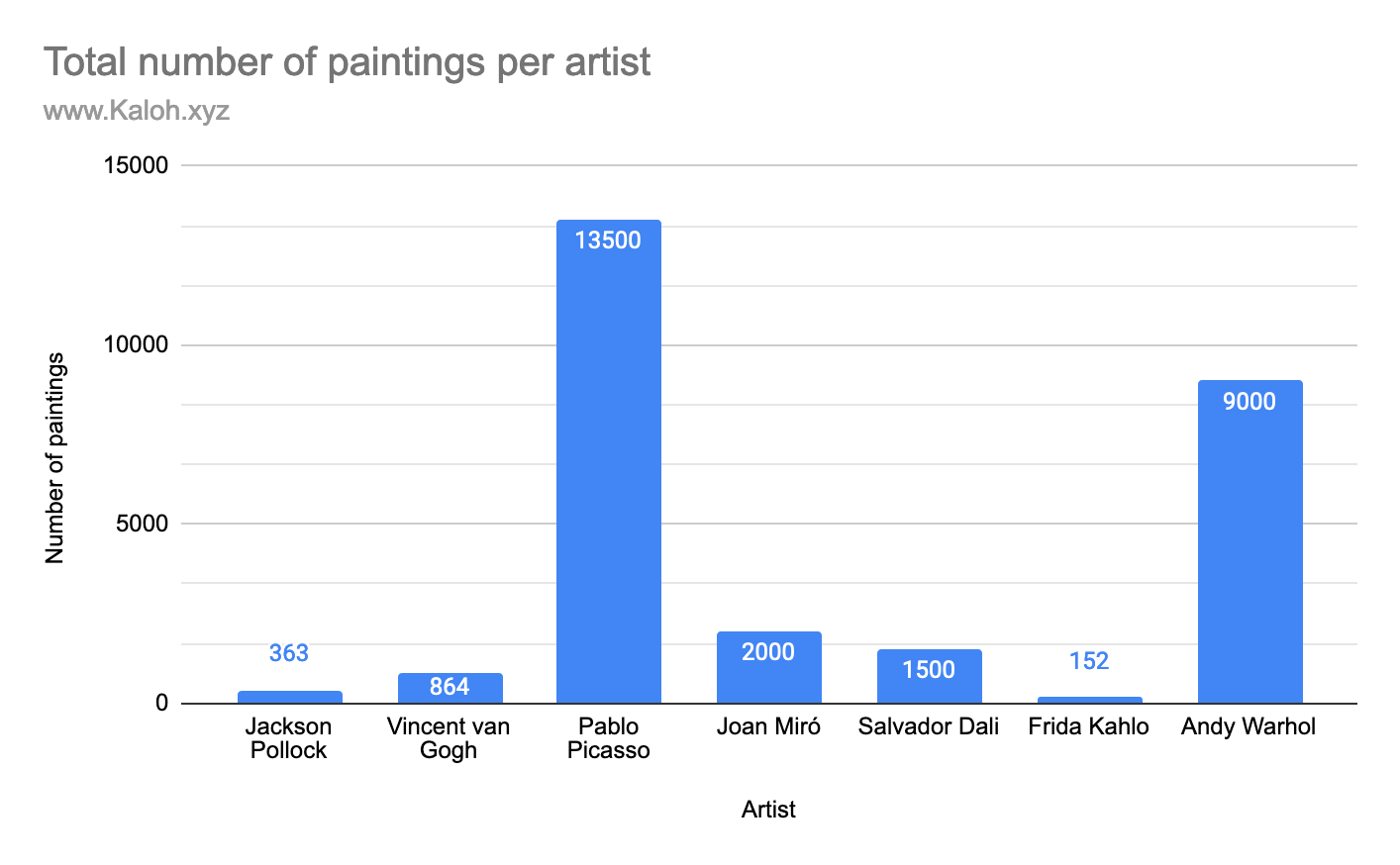

Each artist is different. This is obvious regarding the art style, techniques, and inspiration but not so obvious when it comes to efficiency and productivity.

The reality is that some were highly productive, like Picasso (1300), while others produced fewer works, like Frida Kahlo (152)1.

However, during Picasso's long life -- he died in 1973 at age 91 -- he is estimated to have completed 13,500 paintings and around 100,000 prints and engravings.

Source: Famous Picasso Paintings: 7 works that captured our imagination2

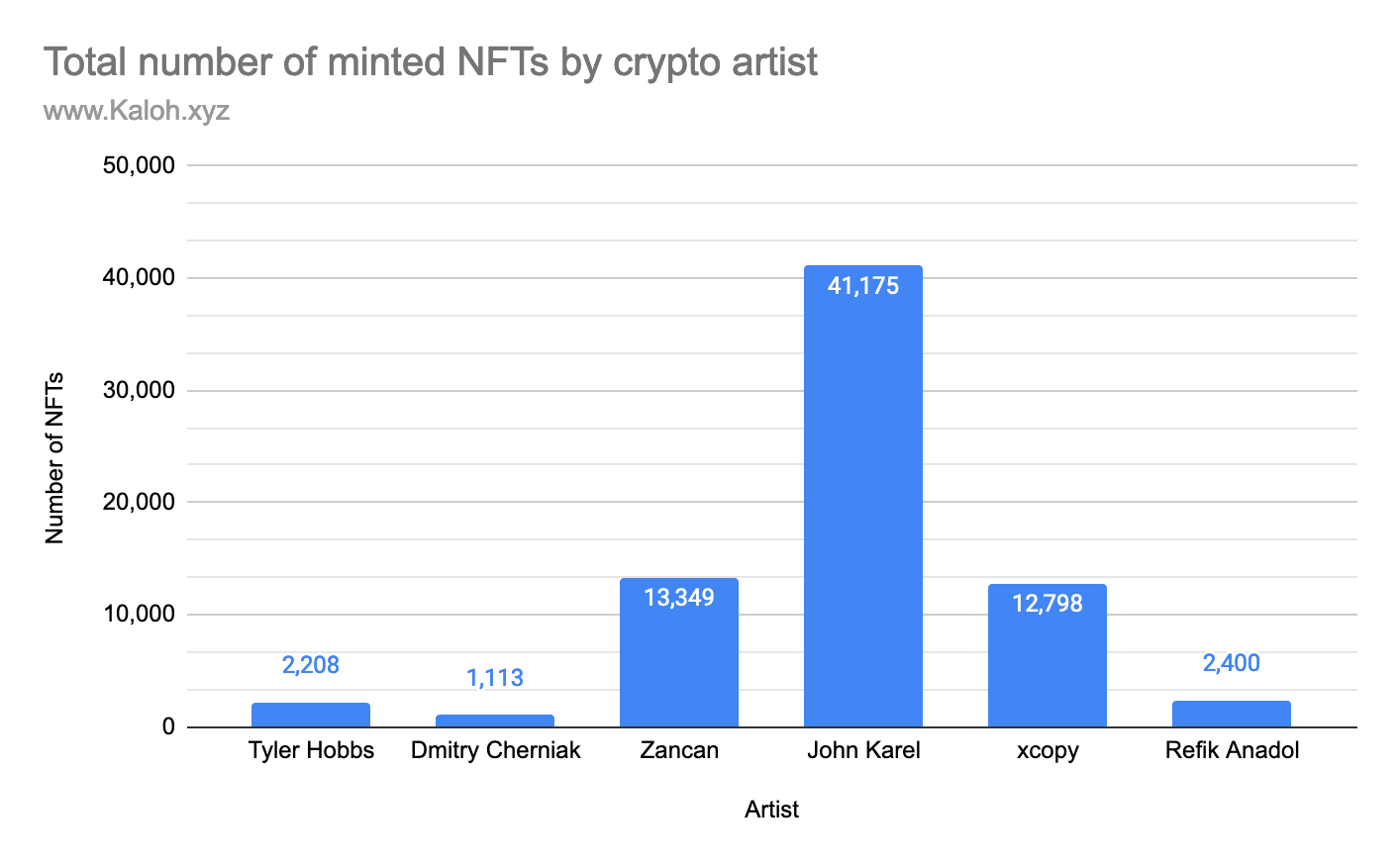

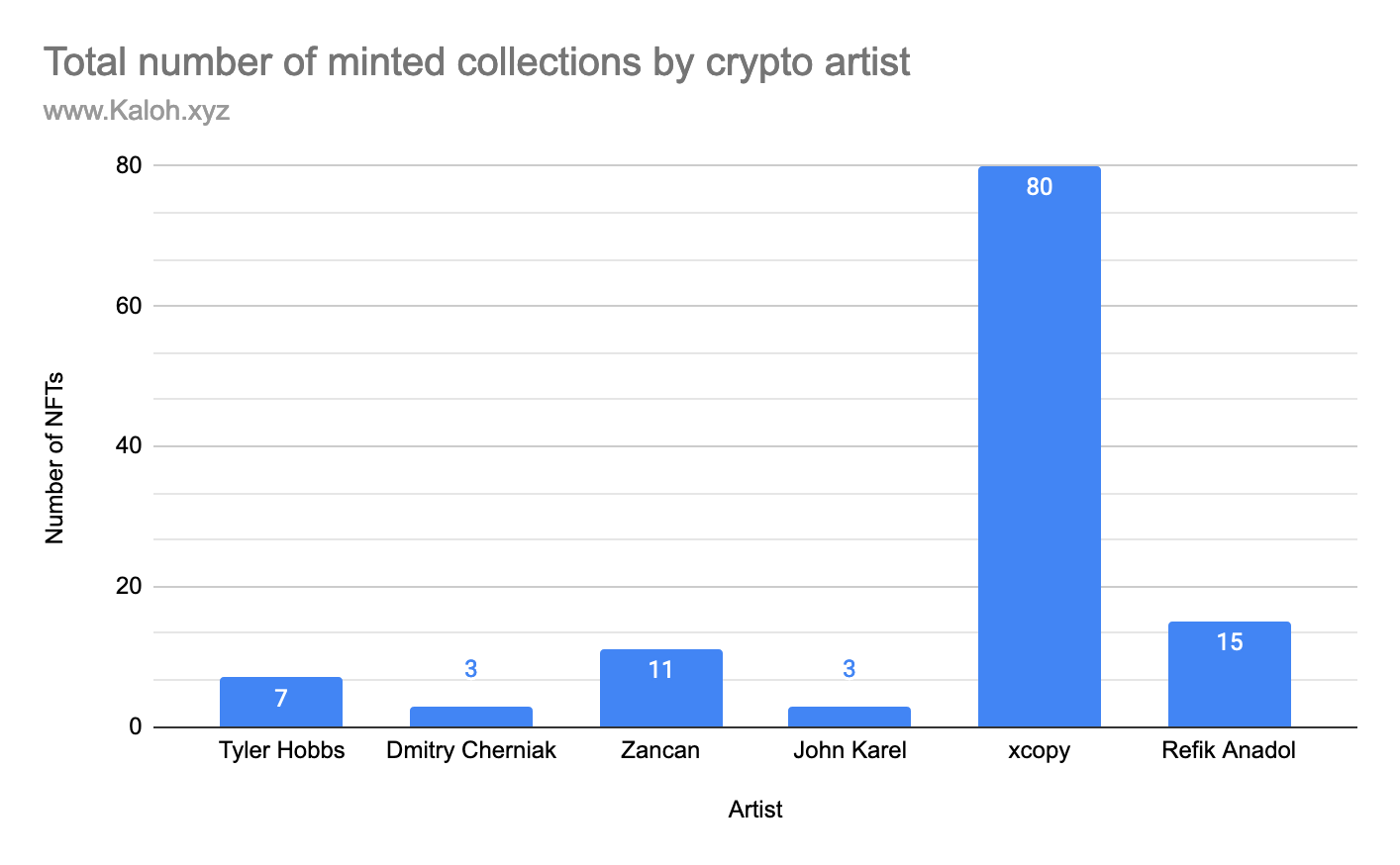

Let’s compare those numbers with the total number of NFTs created by some of the most popular crypto artists (so far).

Generative artists supply

Colossal difference —even if we ignore John Karel and his skeles. But we can’t compare apples to pears.

Generative art and NFTs bring new options that must be mentioned and understood before making this comparison.

Advantages of generative and digital art related to supply

Physical space

No physical or storage space is required to create digital art, while the need for space might slow down an artist's production in the physical art world. This is also relevant for collectors, as they don’t require dedicated storage places.

Distribution

The need for transportation, insurance, and protection of physical artwork might delay or affect an artist's creative process. The blockchain, NFT marketplaces, and crypto-wallets take care of distribution faster and smoother than when dealing with physical goods.

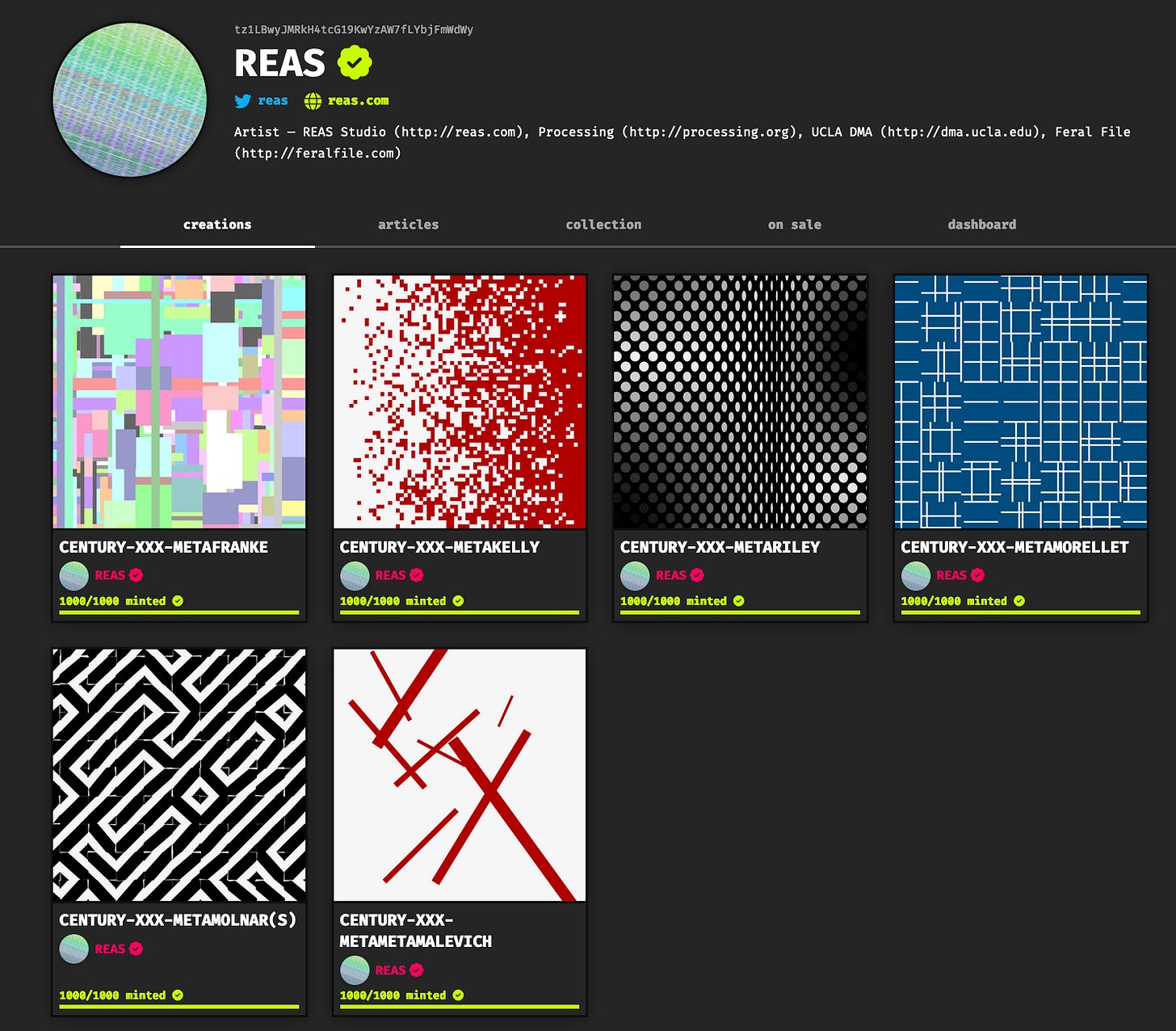

Algorithms and Automation

Although coding an algorithm isn’t easy, once an artist creates one, it can quickly generate thousands (even millions) of creations. Such automation and scalability are impossible with physical and traditional art.

The closest to that kind of production capacity would be when an artist creates a studio or an art factory with hundreds of collaborators to produce work under his signature. Even those cases require complex logistics and time, still not comparable to creating art in the digital realm through algorithms.

Blockchain dynamics

Blockchain dynamics affect supply in ways that aren’t possible with physical art. For example, the burning mechanism is an interesting way to shorten supply, either by design or as an engaging way to interact with collectors.

Riiiiiis offered allowlist spots to anyone that burned one of his previous artworks.

Artists also have complete visibility of their top collectors and can create airdrops or special gifts. While distributing these pieces would be a pain in the real world, it is possible with just a few clicks in the blockchain world. This simple process is another reason why artists might create extra pieces and end up with ample supplies.

With these innovations in mind, we need to think about supply differently.

Artists shouldn’t be limited, and experimenting and taking advantage of technology should be ok or encouraged.

I propose two frameworks or mental models to better digest 1) counting the artist’s supply and 2) deciding the sizing and supply (as an artist). These two ideas came to me from discussions with my readers over Discord.

How to effectively count generative artists’ supply?

What about…

1 collection = 1 artwork?

or

1 algorithm = 1 artwork?

The digital artists’ chart looks much closer to the traditional artist's chart if we take minted algorithms or collections instead of minted individual NFTs. Keep in mind NFTs came to life in 2014 and have been popular for less than three years.

Open question: Creating a digital collection, or generative art algorithm is comparable to creating a painting?

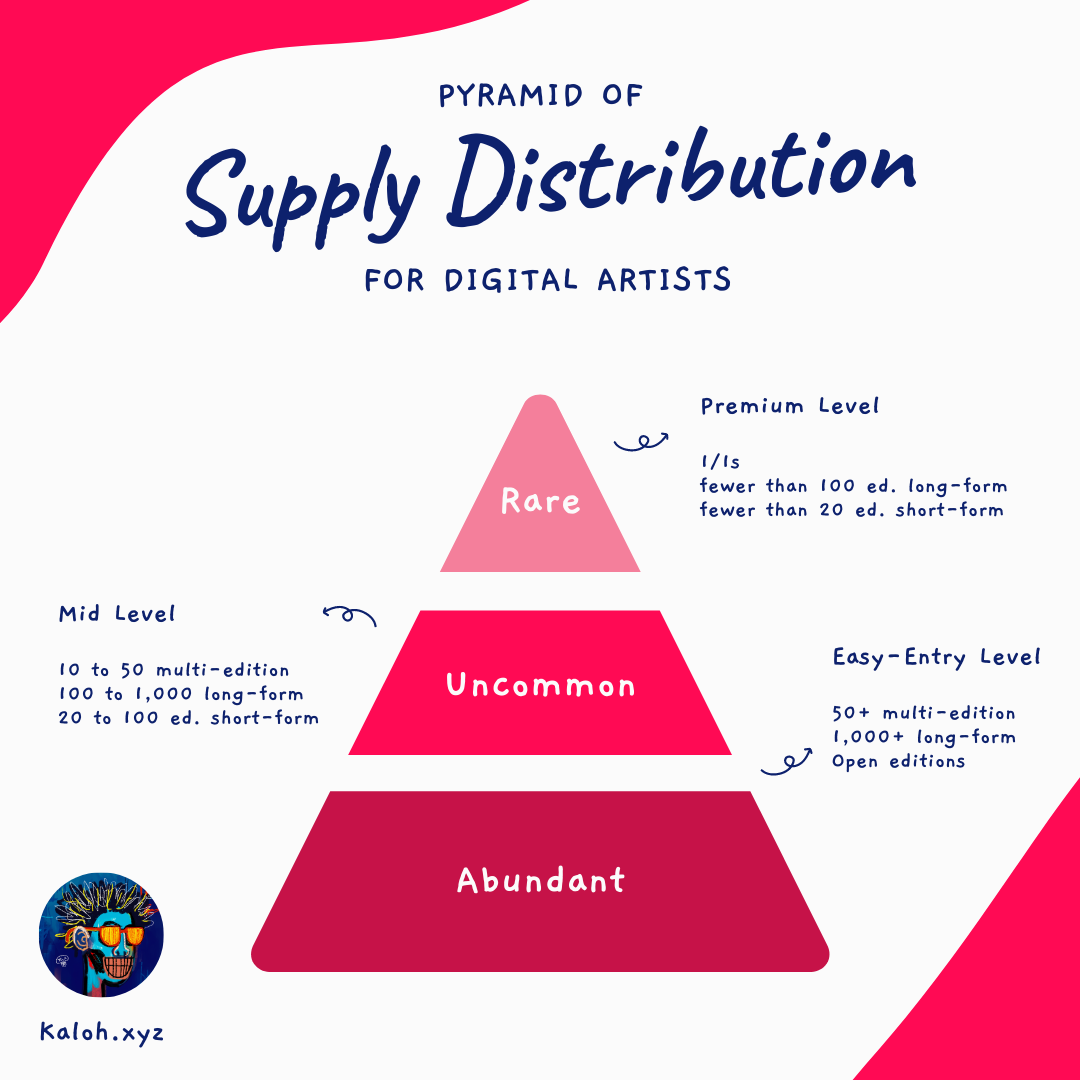

Supply Distribution Pyramid

Artists might find themself debating their sizing strategy. There are many factors in this equation, sometimes, there is not much flexibility for technical or artistic reasons, and other times when working with a gallery, platform, or curator, they might not have complete control over these decisions.

Nevertheless, if you're looking for a guide to navigate your sizing so that more collectors can collect your art, this might help. This could be useful to collectors, too, as we can make collecting decisions depending on our goals when not looking at aesthetics only.

Abundant or Easy-Entry Level

Supply size: 50+ multi editions or 1,000+ 1/1/X, open editions.

Goal: this group is accessible for anyone to collect and feel part of the artist's journey.

The concept is simple. Create artwork that is accessible so your art can be collected by anyone, not just millionaires, institutions, or funds. Airdrops and collecting rewards could be in this group. Open editions and big supply drops don’t necessarily mean these pieces won’t be valuable in the long term.

Also, this could be an effective way for artists to expand their audience, and maybe these collectors will continue collecting in the future.

Uncommon or Mid Level

Supply size: 10 to 50 multi-editions, 100 to 1,000 ed. long-form, or 20 to 100 ed. short-form.

Goal: Upside for collectors. Artwork in this group could eventually make it to the rare group.

This level is the most flexible one; ideally, some of these pieces could eventually make it to the Premium level (in terms of value). This group is for fans capable of spending a bit more, but also for those willing to support artists with some expectations of the art going up in value in the long term.

Rare or Premium Level

Supply size: rare pieces (1/1s or small 1/1s collections less than 100 pieces).

Goal: Produce very scarce pieces that could eventually be worth a lot in part because of how rare they are.

These are acquired by top collectors, institutions, and museums —in a perfect world.

This pyramid isn’t a guide to price your art; it applies to both up-and-coming and established artists. Pricing is not part of this model, as price ranges vary per artist, style, blockchain, marketplace, etc.

In the long term, the market will adjust, and it will be easy to spot the three levels by collectors.

It is fascinating how collectors can have such diverse opinions about supply. Some advocate for short supply to preserve the artist’s value, while others are big advocates of extended editions and are happy with artists reaching more collectors.

Obviously, there is a limit, and it is wise for artists to at least give their edition sizing and release cadence some thought. Nevertheless, I think producing high-quality work and having intent in each piece and collection is more important.

Analyzing the supply will always be essential for collectors looking to profit. However, I firmly believe we shouldn’t count the artist’s supply as the total of individual pieces but more as independent collections. The 3-level supply distribution pyramid might be helpful to better structure artists’ collections without punishing the creator’s urge to produce and share their work.

There are no correct answers to this topic, so I would love to hear your thoughts and ideas below!

Until next time,

- Kaloh

If you enjoyed this issue, consider subscribing to Kaloh’s Newsletter to receive my articles for free in your inbox. For the full experience, become a premium subscriber.

What you’ll get:

Receive premium and public posts.

Access to my private Discord server with over 150 NFT enthusiasts.

Participate in monthly NFT giveaways.

Frida Kahlo and her paintings - https://www.fridakahlo.org/